Art New England : Re-Entry

The Saint

By Carl Little

Maine Home & Design

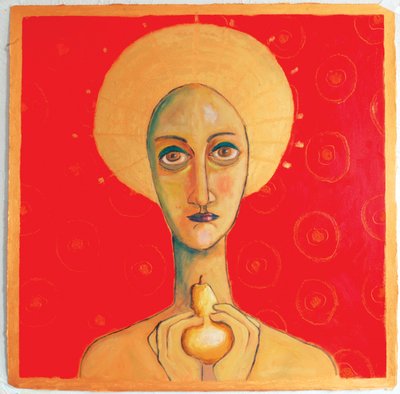

Saint Bearing Pear, 2015, acrylic, oil bar and oil pastel on paper, 36 x 36″.

Alison Goodwin has always had a wonderful way of channeling the likes of Klimt, Hundertwasser and Giotto in translating her surroundings—places and the people in them—into art. The work in this show, around 20 paintings and several drawings from 2014–15, confirms Goodwin’s penchant for the decorative and the symbolic. Working in acrylic, oilbar and oil pastel, she produces stylized landscapes, still lifes and portraits.

Just Before Storm offers a fairly standard Maine coastal scene—ocean, islands and rocky coastline—in a manner that removes it from the ordinary. The water is rendered as a swarm of biomorphic shapes, the rocks as irregular red geometric blocks. The islands have a Hartley look, chunky and dark. One thinks of Brita Holmquist, Eric Hopkins and other painters who play expressive variations on the seascape.

The leafy floor of the forest and the bright tree tops in Late October Trail have a mosaic-like quality that recalls Klimt’s art nouveau period. Goodwin contrasts these patterned areas with a stand of stark limbless trunks and the simple outline of a mountain in the background.

The exhibition features several floral still lifes set against patterned backdrops. In Lupines and Pomegranate, the purple blossoms of that early summer flower emerge from a stately vintage vase. Nearby, a halved pomegranate reveals its seeds. The composition is slightly and appealingly off balance.

Goodwin has cited her Catholic upbringing for the haloes and other religious imagery that appear in her portraits. Saint Bearing Pear offers a wide-eyed, oval-faced woman presented in a classic icon manner, a broad halo encircling her head. The golden tones of her headpiece and flesh are set against a bright red backdrop that owes something to Matisse.

Born in Montreal, Goodwin has lived in various parts of New England since the age of nine (her family moved to Portland in 1968). The title of this, her eighth solo show at Greenhut (she started exhibiting with the gallery in 1989) refers to her return to Maine after living in Vermont for some years. This gem of an exhibition makes for an inspired homecoming.

The Canvas

The Saint

By Carl Little

Maine Home & Design

Carl Little

Alison Goodwin’s Saint Fisherman

In religious paintings, a nimbus of gold encircling the head of a figure signifies holiness—a mark of the sacred. When the painter Alison Goodwin gives a Maine fisherman dashing over the waves in a motorboat one of these golden headpieces, she draws on several centuries of iconography. And in doing so, she elevates this simple man in his waterproof Grundens to, if not sainthood, the status of blessed symbol.

In Goodwin’s rendering, this man in his yellow cap, enveloped in the odors of fish guts and gasoline, is deserving of special honor. “I have a reverence for the way they make a living,” the painter explains, “battling nature day after day.” The fishermen not only keep Maine honest, they “give it a holiness.”

This is Saint Fisherman, intent on harvesting a living from the sea, dashing from his homely bait shack to some last vestige of working waterfront, preparing for another day on the Gulf of Maine. Less heroic than humble, he is more the kin of Marsden Hartley’s beloved Newfoundlanders than George Bellows’s larger-than-life Monhegan islanders.

With the energy of a folk artist, Goodwin employs a bold diagonal—a small boat—and simplified renderings of landscape elements—water, trees, clouds—to create her icon. The spinning-top-like motor churns the sea; bait spills over the edge of buckets; the prow of the boat seems ready to fly over treetops and ledges. With his large hands and determined shoulders, the fisher of the sea goes forth over the waters.

Represented by Greenhut Galleries of Portland for the past twenty years, Alison Goodwin is well known for her saturated, turbulent color and unruly, skewed perspectives. Her original work has been featured in numerous solo exhibits at the Greenhut and in galleries outside Maine, and her prints have been distributed worldwide.

Fish Guts and Gasoline, 2008

Acrylic paint, oil bar and pastel on Arches paper, 56 by 34 inches

Courtesy Greenhut Gallerie

Fruit and Fish: Alison Goodwin’s Reimaging of the Modernist Motif

By Shannon Egan

Gettysburg College

Shannon Egan

Gettysburg College

Alison Goodwin’s painting Cantaloupe (2008) at first appears, perhaps naively, to depict a still life of fruit and flowers on a table: pomegranate, cantaloupe, sunflowers, and a drink. Beneath two rusty red and murky green lines, a diamond pattern demarcates the floor from the wall above. Next to the mottled green and red wall is a view through an open window. Three narrow houses lean precariously to the left; the windows are indicated, almost carelessly, by blocks of watery black paint. Two stylized trees with foliage shaped into bulbous spheres punctuate the row of buildings. Goodwin’s particular style, with its emphasis on a skewed perspective, flattened forms, and broadly applied colors, cannot and should not be read as unsophisticated or unknowing. Rather, Goodwin’s paintings reinterpret the work of some of the most important nineteenth- and early twentieth-century painters. She deliberately evokes the style and subjects of European modernists such as Henri Matisse, Paul Gauguin, and Vincent van Gogh. Each of her paintings recalls the implied formal tension between depicted three dimensional space and the literal flatness of painted planes of color and stylized forms that her predecessors welcomed. Matisse, Cézanne, and others in the late nineteenth century rejected academic norms of picture making (painting realistically through modeling, shade, and one-point perspective). By revisiting these artists’ aesthetic, Goodwin complicates this historical progression and inserts her own mark onto the modernist (and particularly male-dominated) canon.

The diamond shapes on the floor, the circles on the jug, and the daubs of paint on the surface of the melon in Cantaloupe follow Matisse’s interest in pattern and application of bold, unmodulated color. Like many of Matisse’s works, the repetition of shape, line, and color in Goodwin’s painting creates formal rhythms that move the eye around the canvas. Her still life is paradoxically balanced by the scene through the window and the flat but compelling green wall. Because of this emphasis on the wall and the tipping up of the horizontal planes of the floor and table, Goodwin’s composition presents space that hovers between flatness and depth.

While Goodwin’s choice of sunflowers in Cantaloupe evokes van Gogh’s now infamous subject (Vase with Fourteen Sunflowers, 1888), the slice of melon in the immediate foreground of the composition conjures another monumental work of European modernism, Picasso’s Demoiselle’s d’Avignon (1907). Although the dominant subject of Picasso’s painting is five prostitutes, a small still life of fruit with an almost identically depicted slice of melon is presented in the immediate foreground of the painting. Picasso intended for his work to rupture the conventions of painting through spatial ambiguities and assault the viewer with this scene of overt sexuality. His melon slice suggests a blade that both penetrates the space and alludes to the sexual act. In addition to the similarities between the fruit in each painting, the seemingly vaginal incision of the whole melon placed to the slice’s right in Cantaloupe serves as a stand-in for the seated nude at right in Demoiselles, who aggressively faces the viewer with legs spread apart. While Goodwin does not imitate Picasso precisely nor straightforwardly take on his subject, she furthers this bodily symbolism into her still life by pushing two pomegranates snugly between the melon and vase of sunflowers. Pomegranates, traditionally a symbol of abundance, here evoke femininity, sexuality, and a kind of full physicality that Picasso presents more directly. The rounded, tactile, and accessible fruit is offered for the viewer’s visual delectation.

In addition to presenting a metaphorical meal, Goodwin’s Cantaloupe offers complicated formal play via the conflation of indoor and outdoor space. Through the window at right, one sees tall, narrow row houses and towering trees (read in one way, perhaps, as a symbol for a male space?), which make up a fantastical cityscape. Because of the naive presentation of this background, one is uncertain whether this curiously rendered section of the painting truly depicts the outside. Matisse often employed the motif of an open window to suggest a picture within a picture in order to make a painting about painting itself. Good- win, like Matisse, uses this framing device to indicate that this outdoor scene possibly is an ‘‘actual’’ painting within the painting. Reduced to primary colors and simple shapes, the houses and trees offer a strange, almost childlike counterpart to the incised melon. Despite the overall emphasis on flatness in the paint- ing, the marks of white on the glass establish the roundedness of the object. At once these daubs indicate gleaming reflections of a light source and, contradictorily, appear simply as smears of paint. Because each quadrant of the painting works to disrupt the notion of a painting as a congruous whole, Cantaloupe can be classed neither as a traditional still life nor a natural landscape.

Nineteenth-century New England painter Winslow Homer, one of Goodwin’s influences, makes a curious bedfellow to the artists Goodwin evokes in her other work. Although Homer is a contemporary to these painters, his approach and aesthetic differ greatly from his European counterparts. Homer, then, pro- vides a historical, nationalistic link between Goodwin’s pictorial interests in late nineteenth-century art history and her own personal connections to the New England coast. In fish Guts and Gasoline (2008), for example, Goodwin appropriates the subject of Homer’s dynamic painting The Fog Warning (1885) with the palette and style of French nineteenth-century painter Paul Gauguin. Similar to Homer’s composition in The Fog Warning, Goodwin takes the central figure of a man in a fishing boat on the sea as her subject in fish Guts and Gasoline. After acquiring a day’s catch, the fisherman in each painting sails away from the viewer. The stormy waters, ominous sky, and heavy oars present a challenge to Homer’s figure, whose enormous fish and choppy waters tip the boat into a precarious angle. Land is not yet in sight, but a far-of sailboat can be faintly seen on the horizon in The Fog Warning. Goodwin also uses this exaggerated position of the boat to anchor her composition, but the situation appears far less perilous than Homer’s scene. The motorboat takes Goodwin’s fisherman safely toward the warm, wooded shore situated closely at the right of the composition. The clear blue skies punctuated by gleaming white clouds echo the almost joyful froth of the waves created by the momentum of the boat. While Homer’s behemoth fish conjures an arduous tug-of-war between man and nature, the abundant but manage- able catch in Goodwin’s painting does not weigh down the sprightly vessel.

Perhaps most surprising in fish Guts and Gasoline is the gold halo encircling the fisherman’s head. In spite of her fetid title, the figure is no longer an ordinary fisherman. Goodwin deifies him; the halo grants him, however ironically, an extraordinary, saintly status presumably at odds with the commonplace job and the familiar subject. Rather than reading Goodwin’s adoration of the fisherman as a kind of exaltation of the everyday, the style of the halo and its enigmatic presence is reminiscent of Gauguin’s Symbolist paintings. Gauguin portrayed the piety he saw among the peasants of northern France through bold colors and biblical scenes and symbols. His own Self-Portrait (1889) features a halo over his disembodied head. By taking Gauguin’s halo, van Gogh’s colors, Matisse’s pat- terns, and Picasso’s ambiguities of subject and space, Goodwin presents a complicated marriage of particular art historical references. She avoids pastiche and instead finds originality in a careful use of a visual and historical language. Goodwin translates the pictorial concerns of nineteenth- and early twentieth- century artists into a new vision for contemporary painting.

Follow this and additional works at: https://cupola.gettysburg.edu/arthfac

Part of the History of Art, Architecture, and Archaeology Commons

This is the publisher's version of the work. This publication appears in Gettysburg College's institutional repository by permission of the copyright owner for personal use, not for redistribution. Cupola permanent link: https://cupola.gettysburg.edu/arthfac/4

This open access article is brought to you by The Cupola: Scholarship at Gettysburg College. It has been accepted for inclusion by an authorized administrator of The Cupola. For more information, please contact cupola@gettysburg.edu.